The Societal Nature of Man in Robinson Crusoe

Posted On February 15, 2017

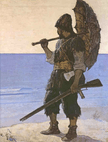

Daniel Defoe’s classic work Robinson Crusoe has long been a favorite volume in my library. The exciting adventure of the man stranded for nearly thirty years on a deserted island and his struggle to survive is one that many are familiar with, even if they have not read the book. Defoe’s magnum opus overflows with themes and motifs, some more predominantly than others. The tale is heavily rationalistic with a Protestant flavor. Crusoe survives through strict discipline, hard work, and frugality. He views the natural resources around him in a utilitarian manner. But there is one area that displays the romantic undercurrent flowing through the narrative, and I want to explore that area briefly.

Recently, I reread Robinson Crusoe for a Great Works class here at Reformation Bible College. In doing so, I devoted attention to Defoe’s emphasis on community. Although I had previously noticed this motif, the individualistic nature of our society makes the theme of community especially relevant.

Given the premise of a man stranded on an island by himself, community is not an immediate idea that comes to mind. However, it is the sheer absence of any society that proves to be the greatest nemesis to our hero. He successfully meets and overcomes the challenge of food, housing, and clothing; he even finds methods of making pottery, a luxury to a man in Crusoe’s dire situation. He establishes three houses and keeps a cave as an emergency storage unit. He grows wheat and makes bread. He also tries to brew beer, though he is unsuccessful in this endeavor. But despite his abilities in these areas, he cannot overcome his loneliness.

I’m reminded of a line in Luis Buñuel’s 1954 cinematic version of Robinson Crusoe where we hear the narrating voice of Crusoe cry out in anguish, “Somehow I must escape this tomb!” For Crusoe, all of his work is pointless if he has no one to share it with. He might as well be dead. Ultimately, Providence intervenes to provide Crusoe with companionship in a cannibal captive whom he dubs Friday. It is an awkward relationship at first due to language barriers, but eventually Crusoe and Friday become friends. As a result of his extreme isolation, Crusoe relinquishes some of the prejudices of his day with regards to Friday, and later toward the Catholic Spaniards who appear later in the book. This is where we see the utilitarian rationalist elements (he needs their help, so logically he is friendly toward them) and the humanitarian romantic elements (he sees the importance and worth of his fellow man). Both are true, yet both are an incomplete picture of the circumstances.

The takeaway? We need to place a greater emphasis on community, especially in the church. I believe there is a healthy type of individualism, one that understands all people as individuals with God-given rights and dignity (as opposed to collectivism, which values the group over the individual). However, we need to avoid an individualism that sees no need for society. Scripture is clear that from the beginning God created man to have fellowship (Gen. 2:18), and that haunting lack of fellowship is the great curse for Robinson Crusoe.

— D.M. Gibson is a Sophomore at Reformation Bible College.